In 1918, two years after she’d graduated from the University of Vermont with a degree in home economics and education, Marjorie E. Luce accepted a position with the university’s agricultural extension service that over the next decade or so would take her all over the state to talk and teach about everything from the best way to can liver to “Making Your Home Restful and Attractive.” Her work was in keeping with the mission of the “Country Life Movement,” which aimed to bring the benefits of city living to rural communities—and vice versa.

This movement had been fueled by the findings of a blue-ribbon commission appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt during his last full year in office. Its report, published in 1911, called, among other things, for the construction of new and improved roads and the expansion of agricultural extension programs—just like the one that would come to employ Marjorie Luce. (In time Vermont would have its own Commission on Country Life

The tearoom movement was also taking hold across the nation in the 1920s, fueled on one hand by the Great Depression and by Prohibition on the other. Luce, seeing opportunity in the convergence of these two movements, began talking with her two sisters about building a roadside tearoom and summer hotel on the concrete road from Burlington to Montpelier. Barbara M. Luce worked for Luce Brothers, Inc., the family’s well-established clothing store in Waterbury, and Anna Luce Maxwell was the matron of the Vermont State Hospital, also in Waterbury, and all three women planned to keep their respective jobs while tending to the lodge in season with the help of an on-premises manager. In 1930 the three women settled on the perfect spot for their establishment—the “twist” in U.S. Route 2 at the top of French Hill in Williston—and construction began in October of that year.

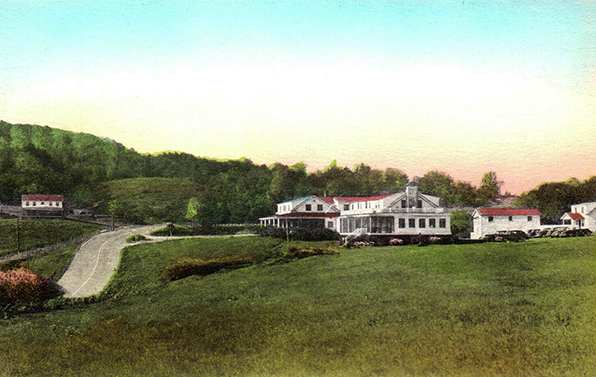

Twist O’Hill Lodge opened on June 10, 1931. It offered breathtaking views of Vermont’s Green Mountains, with the Winooski Valley in the foreground and Mount Mansfield, the state’s highest mountain, in the background), eight “sleeping rooms,” and a combination dining and living room with hardwood floors for dancing. The lodge, furnished throughout with antiques, was surrounded by screened-in porches wide enough to accommodate tables for leisurely lunches and tea—even dancing. But that wasn’t all. The three Luce sisters also built a three-car garage for the use of guests, a four-bedroom house for the lodge’s employees, and two small tourist cabins with more planned for the future.

At the time it opened, Twist O’Hill Lodge could accommodate 50 guests at a time. Its first “Special Sunday Dinner” offered a veritable cornucopia of food for the Depression-friendly price at $1.00. Diners had their choice of chicken consommé or a small tray of sweet-pickle chips, celery, and cut cantaloupe and, as entrées, a minute steak with mushroom sauce, Southern-style roast ham, or fried chicken (25 cents extra). These were served with mashed potatoes, fresh asparagus, an assortment of jellied fruit salads, white and whole-wheat bread, Parker House rolls, and, for dessert, a choice of butterscotch pie, strawberry shortcake, ice cream with a fresh fruit sauce, and assorted cakes. Tea, coffee, and milk were served with the meal.

In 1931, with expansion in mind, the Luce sisters bought a house across the road and an additional nine acres, and three years later they built an addition to Twist O’Hill Lodge that included a new kitchen and dining room, three large fireplaces and three large porches, eight more sleeping rooms, and a downstairs recreation room. They also extended their season by three weeks.

Twist O’Hill Lodge prospered through the 1930s, 1940s (with a break in operation during World War II), and 1950s, even though it had no shortage of competition. There were big hotels in Bread Loaf, Middlebury, Morrisville, Richmond, and Waterbury, and a multitude of other camps, resorts, taverns, and tearooms catering to tourists and travelers. But the Luce sisters found a big fan in Duncan Hines, America’s leading where-to-eat expert, who gushed about their place in his syndicated newspaper column. “Cheerfully burning fireplaces, interesting and inviting furnishings, spacious dining porches, magnificent views, and good food,” Hines wrote, “are some of the things that lure many hungry visitors to Twist O’Hill Lodge at Williston, Vermont.”

In 1959 Marjorie Luce retired after 41 years with the Vermont Extension Service, 35 of them as the state’s home demonstration leader (a position she’d created in 1924). But things soon began slowing down at Twist O’Hill Lodge, and its last full summer season came in 1964. It quietly closed for good after the 1966 season, and in 1968 Marjorie Luce sold the property to W. Howard Delano and Gardner Hopwood, who converted it into the Pine Ridge School, a private boarding school for teenage boys with learning disabilities, which opened later that year.

As for the Luce sisters, Barbara died in 1975 at age 74, Anna in 1978 at age 86, and Marjorie in 1989 at age 94. In 2009 the Pine Ridge School, faced with declining enrollment and saddled with a mountain of debt, closed. Five years later a reporter observed that many of the buildings on the 128-acre campus looked “tailor-made for shooting a zombie apocalypse movie.” The property was eventually purchased by the New England Theological Seminary’s Institute for Church Planting for $1.5 million—$2 million under the initial asking price.

kawijitu

Maple Rag-a-Muffin Dessert

The Twist O'Hill Lodge in Williston, Vermont, found a big fan in Duncan Hines, America’s leading where-to-eat expert, who gushed about the roadside tearoom and summer hotel in his syndicated newspaper column. “Cheerfully burning fireplaces, interesting and inviting furnishings, spacious dining porches, magnificent views, and good food,” Hines wrote, “are some of the things that lure many hungry visitors to Twist O’Hill Lodge.” Hines first published this recipe (adapted here from the original) in 1950.

Ingredients

- 1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour

- 3 teaspoons baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 teaspoon cream of tartar

- 4 tablespoons vegetable shortening, chilled

- Scant 1/2 cup milk

- 6 tablespoons unsalted butter, at room temperature

- 1 1/2 cups maple syrup, heated

- 3 to 4 cups lightly sweetened whipped cream or ice cream, for topping

- 1/4 chopped nuts, for garnish

Instructions

Heat the oven to 450 degrees.

In a large bowl, sift the flour with the baking powder, salt, and cream of tartar. 1/2 teaspoon salt, 3 teaspoons baking powder and 1/4 teaspoon cream tartar. Using two knives, a pastry blender, or your fingertips, cut in the shortening until the mixture resembles cornmeal.

Gradually add the milk to the dry ingredients, stirring constantly, to form a soft dough. Roll it out on a lightly floured surface into a circle about 1/2 inch thick. Using a biscuit cutter or a glass, cut into 12 or so 2 1/2-inch rounds. (The scraps can be lightly kneaded together, rolled, and cut.)

Place the biscuits at least 1 inch apart in a well-greased baking dish and dot generously with butter. Drizzle the maple syrup over the biscuits until all of them are coated.

Transfer the baking dish to the 450-degree oven and bake 15 minutes.

Remove the baking dish from the oven. Serve each round while it is still warm with a dollop of whipped cream or a small scoop of ice cream. Garnish with chopped nuts.

In Our Vault: More Recipes from Twist O’Hill Lodge

- Pumpkin Pie

No Comments